The universe. A boundless, awe-inspiring expanse that has captivated humanity for millennia. From ancient myths to modern scientific inquiry, we’ve strived to understand its origins, its evolution, and our place within its grand tapestry. The Big Bang theory stands as the dominant cosmological model, a framework attempting to explain the universe’s journey from its primordial state to the complex cosmos we observe today.

But what exactly is the Big Bang? What compelling evidence supports this seemingly extraordinary claim? And, perhaps even more importantly, what fundamental assumptions underpin this intricate model, and how do these assumptions shape our understanding of cosmic genesis? Let’s embark on a journey through the realms of cosmology, exploring the Big Bang theory with a critical eye, acknowledging both its triumphs and its lingering enigmas.

The Big Bang theory, at its core, proposes that the universe originated from an incredibly hot, dense state approximately 13.8 billion years ago. Picture, if you can, all the matter and energy within the observable universe compressed into a volume smaller than an atom – a singularity of unimaginable proportions. From this point of singularity, the universe underwent a period of rapid expansion and cooling, a cosmic explosion that set in motion the formation of stars, galaxies, planets, and ultimately, everything we see around us. This expansion, remarkably, continues to this day, a testament to the universe’s dynamic and ever-evolving nature.

One of the cornerstones of the Big Bang theory is the Cosmological Principle. This principle, a simplifying assumption, asserts that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales. In essence, this means that the universe appears roughly the same in all directions and at all locations.

While this assumption simplifies the complex equations of cosmology, it’s vital to recognize that it’s an idealization. Observations reveal that the distribution of galaxies isn’t perfectly uniform. We see vast structures like galaxy clusters and superclusters, immense collections of galaxies bound together by gravity, which challenge the notion of perfect homogeneity. These structures suggest a level of complexity that hints at the limitations of this simplifying assumption.

Another crucial assumption is the applicability of our known physical laws to the early universe. We extrapolate our understanding of gravity, electromagnetism, and the nuclear forces to conditions of extreme density and temperature, conditions vastly different from those we encounter in our everyday lives. However, it’s entirely possible that at these extreme conditions, our current understanding of physics breaks down. We may require entirely new theories, perhaps involving quantum gravity, to fully comprehend the universe’s first fractions of a second. This is a frontier of active research, a source of profound perplexity for cosmologists, and a testament to the inherent limitations of our current scientific understanding.

So, what evidence elevates the Big Bang theory from a mere hypothesis to a widely accepted scientific model? Several key observations lend strong support to this cosmic narrative. First and foremost is the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. This faint afterglow of the Big Bang, discovered in 1964, permeates the entire universe. It’s remarkably uniform, a compelling piece of evidence supporting the idea of a hot, dense early universe. However, subtle variations within the CMB, tiny fluctuations in temperature, also provide invaluable information about the early universe’s structure and the seeds of galaxy formation. Analyzing these minute variations is a complex and computationally intensive task, requiring sophisticated statistical methods and a deep understanding of astrophysics.

Secondly, the observed expansion of the universe, enshrined in Hubble’s Law, directly supports the Big Bang. We observe that galaxies are receding from us, and their recession velocity is proportional to their distance. This observation implies that the universe was once significantly smaller and denser. While the expansion is a cornerstone of the Big Bang, the precise rate of expansion, quantified by the Hubble constant, remains a subject of ongoing research and refinement. Different methods of measuring the Hubble constant yield slightly discordant results, creating a tension within the standard cosmological model that cosmologists are actively working to resolve.

Thirdly, the abundance of light elements, primarily hydrogen and helium, in the universe closely matches the predictions of Big Bang nucleosynthesis. This theory explains how these elements were formed in the first few minutes after the Big Bang, a period when the universe was hot enough for nuclear reactions to occur. The observed abundances of these elements closely align with theoretical predictions, providing further support for the Big Bang framework. However, accurately measuring these primordial abundances is a challenging endeavor, as stellar processes over billions of years can alter the composition of galaxies.

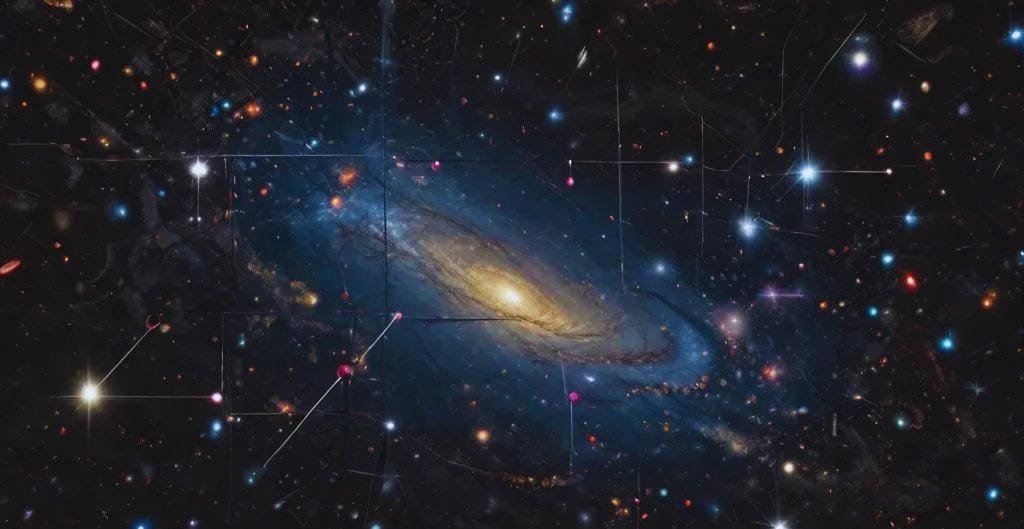

Finally, the large-scale structure of the universe, the intricate network of galaxies, clusters, and superclusters, provides valuable clues about the universe’s evolution. Sophisticated computer simulations, based on the Big Bang theory and incorporating the effects of dark matter and dark energy, can reproduce the observed large-scale structure remarkably well. However, the nature of dark matter and dark energy, which together constitute the vast majority of the universe’s energy density, remains a profound mystery. We know very little about these enigmatic components, representing a significant gap in our current understanding of the cosmos.

The Big Bang theory, while remarkably successful in explaining a wide range of cosmological observations, is not without its challenges. The nature of dark matter and dark energy, the singularity at the beginning of time (which represents a breakdown of our current physics), and the precise details of inflation (a hypothetical period of extremely rapid expansion in the early universe) are all open questions that continue to fuel cosmological research. Furthermore, alternative cosmological models exist, though they currently lack the robust observational support that the Big Bang theory enjoys.

Conclusion:

The Big Bang theory offers a compelling and comprehensive framework for understanding the origin and evolution of our universe. While certain assumptions underpin this model, a wealth of observational evidence, including the cosmic microwave background radiation, the expansion of the universe, the primordial abundance of light elements, and the large-scale structure of the cosmos, strongly supports it. However, significant challenges and open questions remain, particularly concerning the nature of dark matter, dark energy, and the universe’s earliest moments. Continued research, both theoretical and observational, is crucial to refine our understanding of the universe and to unravel the remaining mysteries of the Big Bang.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

Q: What is the Big Bang?

A: The Big Bang is the prevailing cosmological model describing the universe’s origin from an extremely hot, dense state approximately 13.8 billion years ago. It’s not an explosion in the traditional sense, but rather a rapid expansion and cooling of the universe from this initial singularity.

Q: What is the evidence for the Big Bang?

A: The primary evidence includes the cosmic microwave background radiation, the expansion of the universe (Hubble’s Law), the abundance of light elements (hydrogen and helium), and the large-scale structure of the universe.

Q: What are some of the key assumptions of the Big Bang theory?

A: Key assumptions include the Cosmological Principle (homogeneity and isotropy on large scales), the applicability of known physical laws to the early universe, and the existence of dark matter and dark energy.

Q: What are some of the challenges and open questions related to the Big Bang theory?

A: Major challenges include understanding the nature of dark matter and dark energy, explaining the singularity at the beginning of time, and determining the precise details of inflation.

Q: Are there alternative cosmological models to the Big Bang?

A: Yes, alternative models exist, but they currently lack the same level of observational support as the Big Bang theory. They often address specific aspects of the universe that the Big Bang theory doesn’t fully explain.

Q: How does the universe continue to evolve after the Big Bang?

A: The universe continues to expand, driven by dark energy. Galaxies are moving further apart, and the rate of expansion is accelerating. Stars form and evolve within galaxies, and new elements are created through stellar processes.

Q: What is the ultimate fate of the universe according to the Big Bang theory?

A: The current understanding suggests that the universe will continue to expand indefinitely, becoming increasingly cold and desolate. However, the precise fate depends on the nature of dark energy and the overall density of the universe, both of which are still subjects of research.

Q: What is the cosmic microwave background radiation?

A: The CMB is the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, a uniform radiation that permeates the entire universe. It provides crucial evidence for the hot, dense early universe.

Q: What is dark matter?

A: Dark matter is a mysterious substance that interacts gravitationally but does not emit or absorb light. Its existence is inferred from its gravitational effects on galaxies and galaxy clusters.

Q: What is dark energy?

A: Dark energy is an even more mysterious force that is thought to be driving the accelerated expansion of the universe. Its nature is largely unknown.

Q: Can we travel back in time to the Big Bang?

A: No, traveling back in time to the Big Bang is not currently possible. Our current understanding of physics does not allow for time travel. Furthermore, the singularity at the beginning of time represents a breakdown of our current physical laws.